We promise that not every newsletter will be about the exciting world of archival research1. But with the drop of a new tornado movie trailer during last week’s Superbowl, we thought the timing was good to address one of the topics of that movie – the evolution of Tornado Alley2.

Jen Walton, founder of Girls Who Chase, first mentioned this to me at a recent meeting of the American Meteorological Society. I never doubted it. Who would know better about changes in where tornados are found than storm chasers who sleep with maps under their pillow?

The darkness is not for artistic effect. (Girls Who Chase)

Jen said: “Storm chasers, especially those who have been at it for 20 years or more, are an untapped trove of observational data about how tornado alley may shift in response to climate change or other large-scale patterns. To become a successful storm chaser, one must become a pattern specialist for their particular region and area of interest. Chasers must learn where and how storms typically form in their preferred chase regions, how they typically behave and move, and what to look for to know when something is worth the trouble of chasing.

“Part of what makes capturing severe weather in tornado alley doable for a broad spectrum of chasers - researchers, photographers, videographers, thrill seekers, etc. - is the wide open spaces, long flat roads, and expansive views characteristic of the Plains. As we travel east out of the Plains, chasers encounter reduced visibility due to trees or other difficult terrain and an increase in urban areas or higher population centers and consequent traffic and other obstacles. Tornado alley shifting east just plain makes it harder to chase, so these changes over time can not go unnoticed.”

A map of historic tornadic activity (Dan Craggs - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0)

It didn’t take much effort with Google Scholar to find research to back up storm chasers’ hunches. One key paper by Vittorio Gensini & Harold Brooks in the esteemed journal Nature Climate and Atmospheric Science illustrated the general consensus - that the concentration of tornadic activity is moving from the Great Plains into the Mississippi River Valley and the Midwest.

Analysis of 1979-2017 tornadic activity. Red shows increasing activity, blue decreasing.

To be clear, most tornadic activity continues to occur in the Great Plains. This map shows change-over-time, not absolute numbers. (from Gensini & Brooks, 2018)

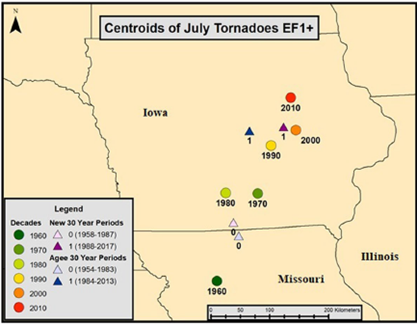

Most of the research on this topic has looked at annual or seasonal trends, which can hide short-term variations. Researchers Trevor Krainz and Shunfu Hu at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville recently published a monthly analysis of tornado activity over the last half-century. They found that the center of tornadic activity may actually be moving northward during some parts of the year, especially in the summer. For example, the center of July tornadic activity has shifted from Missouri (1960) to northeastern Iowa (2010).

The center of all annual tornadic activity in the central US has moved southeastward in the last 50 years (blue to red dots). (Krainz & Hu, 2022)

But if you look at July only, it has moved northward. (Krainz & Hu, 2022)

Tornadic activity during the summer months has always occurred more often in northern areas as the warm, humid air from the Gulf of Mexico makes its way further north. But what is interesting is that the center of the activity is not moving southeastward as it does during the rest of the year. High tornadic activity regions may not simply be shifting, but also stretching.

This evolution has important implications for those living in its path. The new regions are more heavily populated than the Great Plains, meaning more people are in danger. Also, those areas tend to be less prepared for severe weather due to several factors, not least because tornado awareness hasn’t been as much of a cultural thing. So, for example, homes are less likely to be as structurally sound or have basements.

Why is this happening? Climate change is the phrase on most people’s minds. In their Nature article, Gensini & Brooks agree that climate models may be aligned with this shift, but we cannot yet rule out other natural causes. They said it best in scientist-ese: “It is difficult to isolate these natural vs. anthropogenic factors, but perhaps future attribution studies will be able to describe such causal mechanisms.”

El Niño/La Niña (the ENSO cycle) may also have an influence. Dr. Ashton Cook, previously at the Storm Prediction Center for 19 years, has studied the effects of ENSO on tornado patterns. In particular, they occur farther north during La Niña and further south in El Niño conditions. He presented it at the 2021 National Storm Chaser Summer (A recording is available. Ashton's portion starts at about 6:48 - you don't have to watch all 8 hours to find it, although that would be a fun hazing technique.)

Rejoice, chasers! You are about to enter the land of Buc-ees.

Jennifer added: “The real reason storm chasers notice these shifts is because it disturbs our routines, which we take very seriously. In Spring, when the southern plains are most active, we do Allsup's and Buc-ee's. Then, we shift northward to the central plains, land of Casey's, Love's and Kum and Go (don't think that's real? look it up). There's no Buc-ee's in Missouri, Arkansas, or Lousiana and that's a real problem.”

“There are more of us than you realize, and we’re very good at what we do.” The mission of Girls Who Chase is to inspire, empower, and equip girls and women globally to pursue storms, the sciences, and their passions.

And Now for Something Completely Different

February 29 is a special day, happening only every four years. My graduate school advisor was born on that day. Whenever she did something silly, I told her it was because she was born on a silly day. During five years of (mostly supportive) torture, it was my only rejoiner.

On Thursday, February 29 2024 something cool is happening with the AMS. Weather Band is a global community of weather enthusiasts excited to learn more about and share their love of weather and science, organized by the AMS Community Engagement team. One of their cool projects is the Jamposium. Neither is associated with rocking out nor tasty fruit spreads; it’s a just-as-fun-for-weather-nerds virtual event consisting of webinars and interactive discussions with weather experts. Check out this year’s Jamposium on February 29 - March 1.

Next week: Drones for Atmospheric Research

We acknowledge additional contributions from Jim Bedient and Chad Kauffman.

With apologies to heroic librarians and bureaucrats everywhere.