Below is the first of the special issues WWAT offers to our paid subscribers. Remember, regular WWAT issues will always remain free. And this one is also free for all as a sample. If you’d like to support the American Meteorological Society’s education department, please consider subscribing. Click here for more info on what that entails.

Wind is my favorite meteorological phenomenon. It may due to a tornadic experience as a child, a wonderful memory of feeling a hot wind on my face while sitting on a tropical beach with my wife, or the beautiful motion of wind in Stubio Ghibli movies. I love a warm stiff breeze or a hot wind.

Many moons ago, I was watching a nature documentary on PBS that mentioned the Helm Wind of England. It’s fascinated me ever since, and every year I check to see if anything new has been published about it.

The Helm is a rare and powerful downslope wind that sweeps off one of England’s tallest mountain peaks. As it barrels down a relatively narrow path, it creates a tremendous noise, louder than jet engines, and can cause significant damage. Though rare, it’s remarkably consistent - occurring a few times each year when the meteorological conditions align just right. It’s been observed for centuries, stopping armies and inspiring ghost stories alike.

Let’s turn it over to the Rev. Walton William, who published this description of the Helm in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London in 1837. I like to imagine this being read in Orson Wells’ voice.

On the western declivity of a range of mountains, extending from Brampton, in Cumberland, to Brough, in Westmoreland, a distance of 40 miles, a remarkably violent wind occasionally prevails, blowing with tremendous violence down the western slope of the mountain, extending two or three miles over the plain at the base, often overturning horses with carriages, and producing much damage…

It is accompanied by a loud noise, like the roaring of distant thunder: and is carefully avoided by travellers in that district, as being fraught with considerable danger. Its presence is indicated by a belt of clouds… remaining immoveable during twenty-four or even thirty-six hours…As long as this bar continues unbroken, the wind blows with unceasing fury, not in gusts, like other storms, but with continued pressure.

Cross Fell is the highest peak in the Pennines, a mountain range that runs north–south through the middle of England. The prevailing wind in England typically blows from west to east. However, it sometimes shifts and comes from the northeast. This can occur after a low-pressure system has passed, drawing air counterclockwise around its backside.

This by itself isn’t rare. Mountain ranges often create hot and dry winds on their downslopes (foehn effect). As the approaching air rises above the mountains, it cools and its water vapor condenses, forming clouds and precipitation on the windward side. By the time the wind passes the top, it has become much drier and warmer (heat being released during condensation). It then descends the opposite slope, gaining speed (thanks, gravity) and additional heat (adiabatic compression). The result is usually a hot, dry wind barreling down the mountain side1. In the case of the Helm, it can be so strong as to knock over horses and so hot as to blacken leaves and tree trunks.

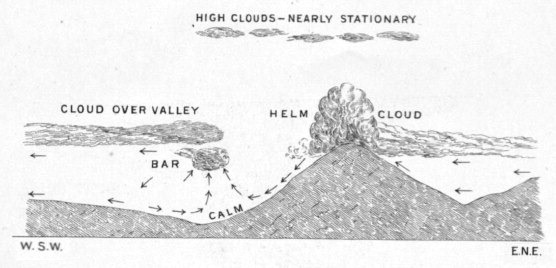

In the image above, one can see how the sudden elevation of the Cross Fell escarpment can push air up extra rapidly. This, plus its extreme height (for England), creates a unique situation that leads to the Helm.

Windspeeds have been recorded as high as 134 mph and have reportedly blown over tractors, removed roofs, and more. The actual wind usually only blows along a strip of land 2-3 miles long and running 20 miles. Though like many who live near a cool landmark, locals all across the region claim to reside “in the helm” when in fact they don’t2.

Homes in the region affected by the Helm were sometimes built with recesses in the outer walls that could be accessed from inside the house. When the warm Helm was blowing, residents placed wet clothes in there to dry.

The Helm Cloud & Bar

It is believed that the Helm got its name from a distinctive cloud formation that appears over the mountaintop, somewhat appearing like a helmet. This is caused by the condensation of the humid air at the top.

It is also associated downwind with a cloud known as the Helm Bar.

As the air descends down the mountain range, it flows in a wave-like pattern. Some of the air rises in the waves, cools once more, condenses and forms a long, smooth, tube-shaped cloud. This cloud appears to hover motionlessly even though air constantly spins through it. A view of the Helm Bar is beautiful enough to warrant being a selling point for property and Airbnbs.

Investigating the Helm

In earlier times, the Helm Wind held a kind of spiritual sway over the local population. Its seeming randomness, strength, hyper-local nature, and continuous roar inspired all sorts of legends and supernatural origin stories of the type that could cure the writer’s block of comic book writers everywhere. The mountain was believed to be haunted by demons that dwelled at its summit. The name Cross Fell is said to come from a cross that the monk Saint Austin placed at the top, attempting to ward off these spirits. Originally called Fiend’s Fell, the mountain was renamed in the hope of banishing its evil reputation. Needless to say, it didn’t work. The Helm abides.

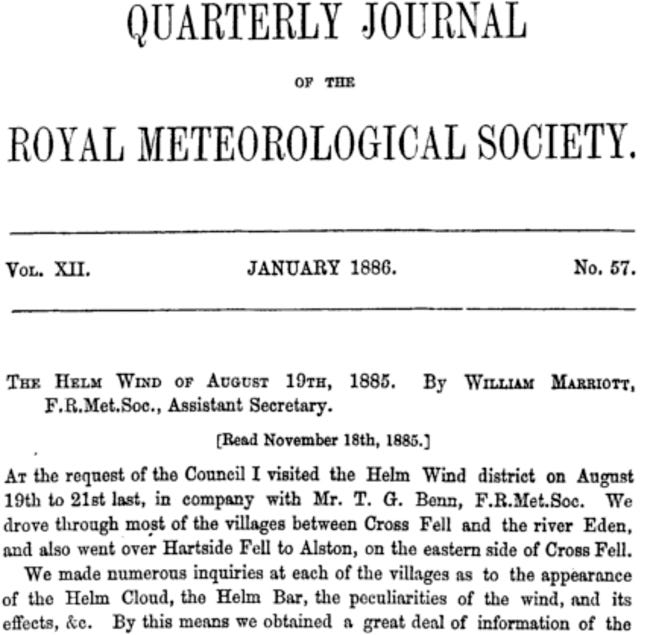

Today, the Helm is well studied, but there were two key periods when scientists made significant progress in understanding it. The first began in 1884, when the Royal Meteorological Society established the Helm Wind Committee. The committee conducted a largely qualitative investigation, interviewing locals and collecting testimonials through notices placed in regional newspapers. Through this effort, they identified some of the first scientific principles behind the Helm, including its connection to strong easterly winds.

The other breakthrough period was in 1937 - 1939 when British climatologist Gordon Manley setup stations to gather consistent data on Cross Fell. Manley meticulously documented wind speeds, directions, temperatures, and pressure patterns around Cross Fell which involved hiking the summit weekly, sometimes in deep snow. He even flew a glider into the wind to confirm his hypothesis (and also break a U.K. glider altitude record at the time).

His work, published in Nature in 1945, provided the first quantitative meteorological analysis of the Helm Wind and confirmed its association with strong easterly flow over the Pennines and the formation of a standing wave pattern.

He also described the Helm Bar cloud in detail and showed how turbulent, gusty winds could descend the western slopes while the Helm Bar remained stationary overhead. Manley’s study transformed the understanding of the Helm Wind from anecdotal folklore into a scientifically grounded case of lee wave dynamics and mountain-induced turbulence.

The Helm in Helm’s Deep

There’s no direct evidence that Tolkien was inspired by the Helm Wind when he created Helm’s Deep, the site of a famous battle in his Lord of the Rings books. However, as a philologist, he often drew deeply on language, history, and mythology. And he had a well-known love of the English landscape. He described Helm’s Deep as “…on the far side of the Westfold Vale, lay a green coomb, a great bay in the mountains, out of which a gorge opened in the hills.”3 Of course, many mountain ranges have places like this. But in England, Cross Fell is the best-known example. But the best evidence could simply be in the title he chose for the location: Helm’s Deep, which has some similarity to our beloved wind. :)

The Helm has indeed has an impact on military campaigns IRL. There is a report of the helm blowing French officers off their horses as William the Conqueror was, well, conquering England4. It led to one of the few English victories in the invasion.

A deeper dive into the natural history and the cultural impact of the Helm can be found in this open access article in the Journal of Historical Geography by Veale, et al. (2014).

About Wind

‘The value of discussing wind lies in what it brings not only, on a theoretical level, to elucidating human relationships with one of the planet's basic aspects of life but also to exploration of how the materiality of wind shapes social practice at a number of fundamental levels'

- Low and Hsu (2007)5, cited by Veale, et al. (2024)6

So ends the first in a series of articles about winds around the world and the role of wind in meteorology. Don’t worry, not all bonus articles will be about the wind. We’ll also have interviews, deeper dives into specific scientific concepts, etc. But wind is one of my favorites, so we’re starting here!

And Now for Something Completely Different

You may have guessed from the structure of regular WWAT issues that I’m a fan of Monty Python. That goes so far as to enjoying Michael Palin’s various travel series. Here, he presents the weather forecast for a New Zealand TV station, a region he frequently visits in his shows. I think we should award him an honorary AMS Certificate of Broadcast Meteorology.

We’ll be back to our regular research articles next week.

Though the helm can occur in the winter as well. When it does, it’s often “the main problem” in town.

https://esmeraldamac.wordpress.com/2012/04/26/the-wind-the-demons-and-the-ghost/

https://acoup.blog/2020/05/01/collections-the-battle-of-helms-deep-part-i-bargaining-for-goods-at-helms-gate/

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2013/apr/21/weatherwatch-wind-clouds-pennines-cumbria

C. Low and E. Hsu, Preface, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13 (2007) Siii.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305748814000474#fn15

Interesting article to read from another Helm enthusiast here (I've been lucky enough to see the Helm Bar twice). In case you've not seen it the Royal Geographical Society's Discovering Britain series includes a walk to celebrate the Helm and Gordon Manley's research and the written guide includes several pages about it: https://www.discoveringbritain.org/activities/north-west-england/walks/great-dun-fell.html