Slow… meandering… depressing… never ending…

These words describe election years. And they also can describe droughts.

We think of droughts as something that slowly sneaks up on us. But they can also pop up out of nowhere, devastate your life, and then quickly depart leaving a barren wasteland. Like a partner who says, “We need to talk.”

A flash drought is a drought that rapidly emerges from nowhere. A common refrain for this newsletter are meteorological terms that are commonly used but not commonly defined. If that’s your drinking game - down a shot because here we go again…

The AMS Glossary of Meteorology defines a flash drought as:

An unusually rapid onset drought event characterized by a multiweek period of accelerated intensification that culminates in impacts to one or more sectors (agricultural, hydrological, etc.).

That’s actually pretty clear: a drought that starts quickly, lasts at least a couple of weeks, and causes great gnashing of teeth among futures traders and stock brokers.

But if we want to study them systematically, we need a quantifiable definition. A new research article about flash droughts by a team of researchers led by Dr. Ali Fallah at UMass Lowell defines flash droughts as when topsoil moisture falls from above 40% of mean moisture levels for that date and area to <20% within 3 weeks or less, and remains there for two to four weeks.

Armed with math, they can now study flash droughts ad nauseum. This is important because such droughts can cause widespread damage - especially to crops. A 2012 flash drought in the U.S. midwest caused over $30 billion in damages. A flash drought is currently impacting farmers in Virginia.

Flash droughts are fundamentally caused by drops in precipitation combined with increased evapotranspiration (ET). The latter is influenced by many things, including cloud cover, air temperature, humidity levels, and vegetation (more vegetation means more ET as the plants take up soil moisture).

The researchers analyzed top soil moisture data from 1981 to 2017 obtained from the North American Land Data Assimilation System v2 (NLDAS). NLDAS is a model using a variety of measurements to estimate soil moisture. One of the variables is surface vegetation. The researchers had a hunch that the modeled vegetation values may contribute some bias to the model. So they created a version of the model that used real vegetation measures taken from satellite data and then compared that to the original.

The new data comes from the Advanced Very High-Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) instrument. It’s such a useful and reliable tool that it’s become something like a stockcar instrument for weather satellites. It’s been installed on dozens of weather satellites operated by many countries since the 1970s.

The AVHRR data is used to create the Leaf Area Index (LAI) - a measure of plant canopy on the Earth’s surface and published through the Global Land Surface Satellite (GLASS) database.

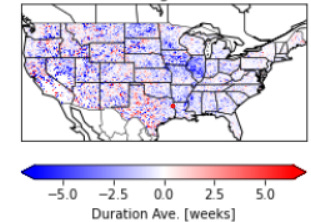

They found the two versions of the model (one with and without LAI satellite data) were similar in determining the regional size of flash droughts. However, the model without LAI tended to underestimate the length of the flash drought compared to the version that used the LAI.

The models also differed in how they detected regional trends in flash droughts (especially in the Great Plains and southeast USA), which is important in determining regional sensitivity to flash droughts.

Flash droughts are quick and short, but can be devastating. This new research looked at the importance of real observations of vegetation to help detect the droughts. Implications are that future flash drought research and models should use LAI, or something similar, especially when looking at long term flash drought trends and patterns.

And Now for Something Completely Different

Gustav Holst is a composer perhaps most famous for his orchestral suite The Planets, which is required background music in just about every major planetarium and astronomy event in the world.

Holst also composed The Cloud Messenger, a lengthy choral work inspired by a 5th-century Sanskrit poem. This piece tells the story of a young man who, after being fired from his job and feeling downhearted while in a long-distance relationship, spots a cloud. Moved, he composes a poem for the cloud to carry over the mountains to his love.

Due to its complexity and length (>40 minutes), it is rarely performed. For this performance, the musicians had to transcribe the piece by hand! I was lucky to recently hear it live. In his opening remarks, the conductor said, “This is not a story of nature but a story of love.” I had never considered clouds to be a romantic communication tool, but love is found where you see it. And now I look at clouds differently.

We acknowledge contributions from Beth Mills.